At home with Just William... and his mum

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“I must warn you, it’s very old-school,” says the writer and curator Adrian Dannatt about the London home his parents moved into in 1955. “It’s pretty much unchanged since then,” he adds of the Victorian townhouse in Canonbury, Islington, that today is both his London base and the home of his artist mother, 97-year-old Joan Dannatt. Alongside the original hessian wallcoverings and wall-to-wall carpets is an extensive and eclectic hodge-podge of artworks and objects that paints a vibrant portrait of a family steeped in creativity – and more than a little eccentricity.

Adrian’s CV includes a decade as the Art Newspaper’s New York diarist, several books on French artist couple Les Lalanne – “I’m the world expert on them, bizarrely enough” – as well as a formative acting job, as the chubby-cheeked child star of the 1970s TV series Just William. “I call myself a resting thespian,” says the author, who has a penchant for charity shops and obscure auction houses. Of his formative TV career, he recalls reading an advert in the newspaper for the role and sending them an appropriately “splodgy, ink-splattered missive”. He adds: “I only told my parents when I got the part.”

In the back-cover blurb of his most recent book, Doomed and Famous, a collection of obituaries “devoted to the odd and outrageous, marginal and maverick”, he describes himself as a “figure better suited to the pages of some minor novel of another era than to the brutal realities of everyday life in the 21st century”.

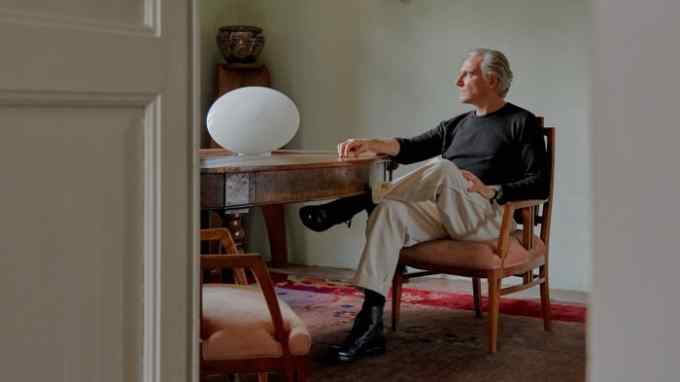

Walking into the Dannatt family home, I’m happily drawn into this world, which begins with two small canvases hung either side of the entrance hallway. “This is my daughter, Clare, and here is Adrian – when he had some hair,” chuckles Joan, pointing to paintings of her then-young children. The portraits were made by Joan in the ’70s but not exhibited until 2015, when she had her first ever solo show, at Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery in Fitzrovia. “Joan was totally opposed to the whole event. I forced it upon her,” says Adrian, sitting in the birdsong-filled sitting room. Joan adds: “My Welsh father – the science fiction author Howell Davies – was very ambitious for my brother and I, and I have produced a son who is equally pushy.” She smiles. “But the exhibition was great. And what was amazing was that we had the opening on my 90th birthday. There was a cocktail bar – which was very popular – and homemade lemon drizzle cakes.”

Joan’s work was also shown more recently at Rebecca Hossack as part of Doomed and Famous: Selections from the Adrian Dannatt Collection – a trio of exhibitions to accompany the book of the same name, and showcasing the art collections that reside in Adrian’s homes in New York, then London and now Paris. Just opened at Galerie Pixi, “the Paris show will include a splendid watercolour by Joan of our apartment courtyard on the Rue de Lappe”, says Adrian, adding that a selection of things will be for sale, priced from 10 centimes to €100,000.

As a whole, the collection reflects “a very personal taste, not to mention a reluctance to spend too much money”. It ranges from the obscure – a Vorticist painting by the Benedictine nun Sister Mary Simon Corbett (found in the same Help The Aged charity shop in Highbury Corner as a beloved pair of £10 handmade Lobb shoes) – to a Jenny Holzer (a plaque bought from her first show in London at Interim Art). “Many were gifts, some were bought in junk shops and at least one was stolen…”

In the mix are family heirlooms and treasures. In Canonbury, an 1891 watercolour of Blackheath Village reveals a sign for Dannatt grocers, while two turn-of-the-century oil paintings (one a landscape, one of a cottage) are by Annie M Dannatt – Adrian’s father’s aunt, “now best known for her watercolour drawings of the butterfly collection of her brother, the fabled lepidopterist Walter Dannatt”. There are drawings by Adrian’s father, the modernist architect Trevor Dannatt, who worked on the Royal Festival Hall; works by his uncle, the property surveyor-turned-abstract artist and music critic George Dannatt; and at every turn, paintings, etchings and drawings by Joan, including one of Fitzroy Square – where she and Trevor had their first home.

In their own sitting room, however, the artworks are those collected by Trevor and Joan, most notably a large pastel-hued abstract painting by the British artist Patrick Heron – “the one great masterpiece in the house”, suggests Adrian, and a reminder, adds Joan, of many trips to see the Herons in St Ives (a few smaller Herons are also dotted around the house, including one in the downstairs loo).

“We mostly bought from people we knew,” she continues. “When we went to exhibitions we would mark in the catalogue which piece we particularly liked.” Thus there are paintings by British artists such as Morley Bury, Bruce Lacey, Kenneth Rowntree and Ivon Hitchens. They reveal a long family history of collecting. “It’s a horrible strain,” says Adrian. “My uncle George Dannatt had a well-known collection of British modernist art. And actually, his father – my grandfather – was a stamp collector who was famously invited to Buckingham Palace to show the king his Chilean stamps.”

Joan’s life-long interest in art – particularly print-making – was fostered at Reading University. “It was a marvellous place. There was a very strong, large man, Roger, who found a lithographic press. And I think it was because I knew about lithography and typesetting that after university I was hired by J Walter Thompson,” she recalls of the advertising agency that at the time also employed Bridget Riley and interior designer David Hicks. “I was the first woman art buyer there, so I was rather on my mettle. Instead of using commercial artists, though, I persuaded art directors to work with fine artists. Like using wood engravings by Eric Fraser for a Rolex watch ad. By going in a different direction, I was able to prove myself.”

In the midst of this Mad Men-esque moment, Joan met her husband through Henry Rothschild, who founded the influential London craft gallery Primavera in 1945. “Trevor had done some architectural work for him, and I’d created printed textiles,” recalls Joan, as Adrian excitedly points out one of his mother’s designs on a cushion, “printed for Heal’s in 1947”. And Trevor Dannatt design details also pop up throughout the house: a sleek cupboard from the 1950s (one of just three made) in an upstairs bedroom; painted blocks of colour (orange, green and blue) in the “rather decrepit bathroom”; the kitchen, “classic 1955”; and a stylish oak ladder leading to the opened-up loft space. (“My children sometimes sleep up there. It’s full of boxes of stuff, and art – like the painting that I bought instead of a Damien Hirst.”) A Dannatt fireplace in the basement dining room, meanwhile, is complemented by furniture from another modernist great – Finn Juhl, the Danish architect who was one of Trevor’s closest friends.

“When I was growing up, posh people – because we were never posh people, we were intellectual left-wing Islington people – all had 18th-century brown furniture,” says Adrian. “When people came here, everybody was dismissive about this ’50s modernist stuff.” Even a heater is something of a modernist icon, designed by architect Wells Coates. “It’s from 1936 – and still in use come winter.”

Other artworks in the hallways have stories to tell between rooms. A curious painting of two men on a picnic blanket (one in a bath; the other playing the clarinet) is by Willie Landels – “a famous design figure, who is still employed by Robin Birley, and was a boyfriend of my mother’s”, explains Adrian. “The family story goes that when my mother said that she was going to marry Trevor, [Willie]threatened to shoot him – and being somewhat Italian, had a pearl-handled revolver to do so. But he didn’t, luckily.” Along a corridor leading out to the garden, a cubist painting resembles a Juan Gris. “But it’s a copy my mother made, which is rather good; she signed it Joan Gris.”

The first floor is “where the real madness begins”, says Adrian, pointing out highlights of his own collection on the landing. There’s a Sonia Delaunay print; a pair of portraits of Cecil Beaton by British painter Patrick Procktor; and “a marvellous unicorn given to me by the artist Richard Wentworth”, the pearlescent ceramic ornament still proudly displaying its RSPCA price sticker: £2. In the bedroom lurks what he refers to as “the wall of shame”, featuring several portraits of himself. “It’s sort of embarrassing,” he says of the display that includes a vibrant ink likeness by young graduate Sacha Floch Poliakoff (the great-granddaughter of modernist painter Serge Poliakoff); a painting by Paul Benney, a regular exhibitor in the BP Portrait Award at the National Portrait Gallery; and a moody, oval-shaped oil by Orlando Mostyn Owen, a teacher at London’s Royal Drawing School.

The garden, meanwhile, is very much Joan’s domain. “She’s a ferocious gardener,” says Adrian. “She’ll be pottering around out there for a couple of hours every afternoon. And then she has her famous rest, from four till six.” In the mornings, however, Joan spends time in her studio – a Trevor-designed extension added to the side of the house in the ’70s, which she has commandeered for her own creative pursuits. “She’s also working on a sort-of memoir,” says Adrian. “It’ll be very anecdotal, with stories about her father, but also her meeting Henry Moore, Dylan Thomas – all sorts of people, and all sorts of Welsh stuff. She’s doing marvellous illustration for it too.”

Does she intend to have another show? “We’re hoping you’re going to come to the hundredth one,” says Adrian, smiling mischievously at his mother. “Oh no, I’m not having it,” declares Joan. “I hope not to get to 100. And I’m not having an exhibition.”

Neither is squeamish on the issue of death. “I was born in that room,” says Adrian, pointing to the sitting room. “I hope to die in that room.” He’s already penned his own obituary – and included it at the end of Doomed and Famous – while Joan has prepared her own coffin, painted with pretty floral motifs. Out of earshot, Adrian confides: “She’s very insistent that she doesn’t want to make it to 100, but I say, come on. I think she has to do it, you know, because she has to beat my dad – and he made it to 101.”

Doomed and Famous: Selections from the Adrian Dannatt Collection is at Galerie Pixi, 95 Rue de Seine, 75006 Paris (galeriepiximarievictoirepoliakoff.com), until 29 October. Doomed and Famous: Selected Obituaries is published by Sequence Press at £25

Comments