How Marc Newson extended his shelf life

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“I wouldn’t consider myself a collector but, you know, I’m 57, I’ve been around for a while. I’ve got a lot of stuff,” says the acclaimed Australian industrial designer Marc Newson. “There’s many, many decades of books and objects. Things that are precious, things that are not but mean something to me. They were all just stowed away in boxes, hidden, and I finally wanted to release them all.”

This is how Quobus, Newson’s latest design, was born. The designer, one of the most influential of his generation, is also one of the most prolific. He’s conceived futuristic aeroplanes and Apple Watches; lent his eye and hand to aluminium surfboards and out-of-this-world lounge chairs; and given life to everything from bottle openers to luxury suitcases. Now he is committing an act of liberation – for all of our stuff.

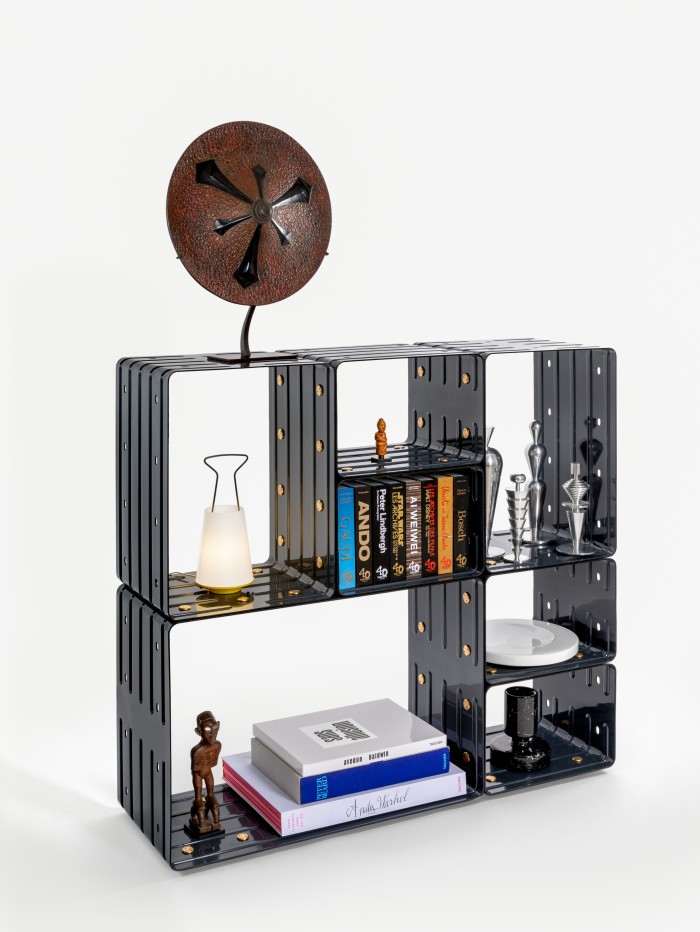

Call Quobus a bookshelf, call it a storage system, call it a room divider or sculpture, or call it what he does: “a landscape which you can populate with whatever you want”. The modular design of differently sized, colourfully enamelled steel cubicles, joined together by golden rivets, is as practical as it is scrupulously refined. “It’s storage on a mundane level, but I thought of it as more than that,” he says. “Each cubicle becomes a sort of dedicated environment. Each one is almost a little shrine.”

The concept began with a commission from the German art-book publisher Taschen, for which Newson was designing display units and shelving for a Milan store in 2015. “The brief was to try and figure out a way of displaying books artfully,” he says from his home office, a converted outbuilding at his Cotswolds home where he has been spending most of the pandemic period with his wife, the stylist and fashion consultant Charlotte Stockdale, and their two children. “I figured if I could get close to solving that problem, I may have gone part of the way to coming up with a system that could work in other environments – domestic ones, for example.”

Newson had never met a bookshelf he gelled with. “I’ve purchased many versions of Dieter Rams’s Vitsoe over the years as it’s great for a variety of purposes but not generally playful. I wanted something playful,” he says. “I liked the idea of adding a sculptural element. It’s primarily functional, with the ability to look interesting in its own right.”

Basically, this is a design Newson could utilise himself. “That’s always the case with the way I work. I’m the yardstick for what I think people might like,” he says. “At the end of the day, I’m a consumer as well. I spend money on these things and I guess I look for something I can’t find, that I’d like to spend money on.” Sitting on the floor, wearing a green hoodie, he swivels his computer screen to show me his own prototype Quobus in action. “This office was an old tack room and the adjoining garage the stables. The shelving is full of automotive paraphernalia: car books, trophies, little awards that I’ve won with my classic cars. It’s kind of corny,” he laughs, playing down the impressive collection of vintage motors in the garage, which includes a rare 1939 Bugatti Type 59.

There’s a simplicity to Quobus, exhibited this year both in Paris and London by Galerie Kreo, that at first sight seems at odds with the fluid futuristic forms for which Newson is known – those stemming from his training in jewellery and silversmithing and his move, almost immediately, into larger furniture that blurred the line between art and industrial design. He remains the only industrial designer represented by Gagosian.

But there are synergies to his most iconic designs: the way he exposes inner elements that are usually hidden, as in his Orgone chair (1993) and Event Horizon table (1992); the exposed rivets and gently curved corners that bring to mind the detailing of the LC1 Lockheed Lounge of 1986 (which at $3.7m took the record for the most valuable work sold at auction by a living designer); and the simple, intuitive functionality that made the Apple Watch, which Newson conjured with his friend Jonathan Ive as part of the software company’s design team from 2014 to 2019. “It’s the perfect continuation of Marc’s work, which is so often defined by clear, direct and naturally rounded lines,” says Didier Krzentowski, co-founder of Galerie Kreo.

It would, Newson says, have been relatively easy to make the shelves in plastic, a composite or a non-ferrous metal, but easy doesn’t feature in the designer’s playbook. “I love the idea of challenging myself and challenging other people to do things that could be deemed almost impossible,” he says. He also likes the “anachronistic, slightly old-school feeling” of enamel, created by a process he describes as “a dark art”. It reminds him of Paris, where he lived for some 10 years. “All the street signs and Metro subway signs are enamelled. There are still companies, mainly in Europe, that specialise in this but it’s fair to say it’s a dying process. It’s expensive and requires a level of expertise and skill.”

In his 2019 exhibition at Gagosian, Newson took his love of enamelling to new heights using the ancient process of cloisonné. One of the most delicate forms of the art, often used on jewellery or small decorative pieces, he applied it on a spectacular scale to armchairs, desks and lounges. Even in China, where the craft is traditionally practised, there were doubts as to whether it could be done as there were no kilns big enough to accommodate the large-scale pieces. In the end, they had to be built.

What drives Newson to constantly challenge what’s possible? “I guess I want to push the boundaries and to satisfy my own curiosity and ego. I need to prove that these things are still possible to do and that there are still people out there that can do them – or can be trained to do them,” he says. “Mostly, I love the process of learning and if, along the way, I’m learning about processes and techniques that have been lost or are being lost, that’s all worthwhile.”

Comments