Xi Jinping’s China: why entrepreneurs feel like second-class citizens

Simply sign up to the Chinese economy myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

This article was originally published as part of the ‘China’s Slowing Pains’ series on 13 May 2019.

Born into extreme poverty in rural China, Liu Chonghua amassed enough wealth selling cakes to the country’s emerging middle class to build himself six European-style castles.

Five are tourist attractions, but the grandest of all was designed as a home: a grey stone structure resembling Britain’s Windsor Castle, built on land the 65-year-old entrepreneur acquired from the government of the southwestern city of Chongqing in the 1990s.

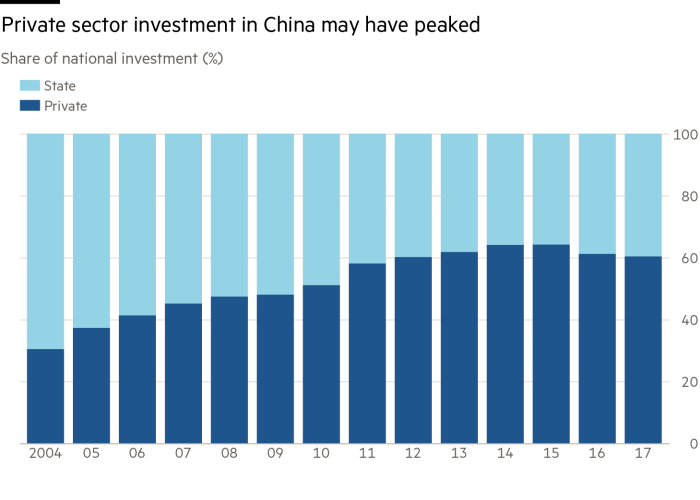

Mr Liu’s tale is one of many rags-to-riches stories in China’s transition to a more market-oriented economy. When Hurun published its first ranking of China’s wealthiest people in 1999, it found just 50 with assets above $6m. The list now features nearly 2,000 individuals worth more than $300m — the tip of China’s sprawling private sector. Non-existent four decades ago, private enterprise today accounts for 60 per cent of China’s economic output and 80 per cent of urban employment in 2017, according to official statistics.

By 2013, Mr Liu, who started selling bread from a cart in the 1980s, had poured Rmb100m ($15m) into his castles, which were close to completion. But then he ran into problems. Sales at his chain of hundreds of bakeries began to fall, leaving him short of funds to finish construction of his castle home.

“When I was younger I didn’t fear the heaven or earth,” says Mr Liu, strolling around the grounds of one of his creations. “Now I feel a kind of formless pressure.”

After two decades of near double-digit expansion in gross domestic product from the early 1990s, China’s economy has been more subdued for most of this decade. That slowdown has become more pronounced — last year’s 6.6 per cent increase in GDP was the weakest since 1990 — a process that has deep implications for business, society and politics in the world’s second-largest economy.

The deteriorating sentiment among private business owners such as Mr Liu strikes at the heart of one of the causes of slower growth. Many entrepreneurs believe that decades of economic reform has stalled — and in some cases gone into reverse — since China’s President Xi Jinping assumed leadership of the country in 2012. The phrase they often use to describe the shifting mood is guo jin min tui, meaning “the state advances as the private sector retreats.”

There are signs that Mr Xi’s strategy to place state-owned companies at the heart of the economy is weighing down the private sector, which has been responsible for such a large part of China’s dynamism over the last four decades.

The most striking indication of the choice in favour of state-owned companies has been a “stark reversal” of a decade-long trend of increased bank lending to the private sector, according to Nicholas Lardy of the Peterson Institute for International Economics. State-owned companies secured 83 per cent of bank loans in 2016, up from 36 per cent in 2010, leading to the “crowding out [of] private investment”, he says.

The trade war with the US has compounded the woes of Chinese entrepreneurs. Private companies account for 90 per cent of exports and Washington’s decision to impose tariffs on Chinese exports has unnerved the country’s equity markets, further eroding private businesses’ ability to raise money. The number of people making the Hurun list’s Rmb2bn threshold last year fell by 237 from the previous year to 1,893.

The rift between the public and private sectors was exposed when an article slamming private business by an obscure former banker went viral last year on Chinese social media. According to the author Wu Xiaoping, the private sector had completed its “historic task” in helping state-owned companies to develop and that it was time for it to start “fading away.”

In previous years, the suggestion would have been too far-fetched to garner attention. But it hit a nerve last summer after President Xi Jinping signalled that Communist party branches should have a greater say over corporate governance, and oversaw the abolition of presidential term limits, making it possible for him to remain top leader for life. “It felt like history was going backwards,” says one Chongqing entrepreneur who asked not to be named.

There were even signs that Mr Wu’s prediction was becoming a reality, with the unravelling of a popular strategy to raise funds by pledging shares as collateral for loans. As their share prices fell over the past year, more than 60 listed companies were forced to sell significant stakes to state-owned groups. In some cases, the companies sold majority stakes and were effectively nationalised.

“Ten years ago entrepreneurs were celebrated because the government wanted to create employment, now they are no longer special,” says Sonja Opper, an expert on China’s private businesses at Lund University in Sweden.

The recent political history of Chongqing, a bustling metropolis of 8m whose numerous skyscrapers rise sharply from the banks of the Yangtze river, might make it an unusual standard-bearer for economic policy in the Xi era.

Bo Xilai, who became party secretary in Chongqing in 2007 and was once considered a rival challenger to Mr Xi in the race to lead the Communist party, was felled by a lurid corruption scandal in 2012. He was sentenced to life in prison. His successor Sun Zhengcai was also handed a life sentence for corruption last year after a separate graft scandal.

But the city, whose location makes it a transport and logistics hub for central China, has been a laboratory for the state-centric growth model that has been so successful in maintaining China’s growth since the global financial crisis. Chongqing became the country’s fastest-growing city through rapid urbanisation and increased state-led infrastructure spending.

As the developed world struggled through recession, the city boomed: Chongqing’s GDP surged by 17 per cent in 2010 alone. With Mr Sun in charge from 2012, Chongqing maintained double-digit growth. Both leaders oversaw the construction of thousands of kilometres of roads and more than 60 buildings taller than 180m — the height of London’s Gherkin — creating a skyline rivalling Manhattan’s.

Many private companies in Chongqing, such as Mr Liu’s bakery business, benefited from the investment boom as soaring construction sector wages stimulated consumption. Another success story was Tu Jianhua, a contemporary of Mr Liu and the founder of one of Chongqing’s top private companies, motorcycle manufacturer Loncin, who saw his wealth grow from $1.3bn in 2013 to $2.4bn in 2017, according to Hurun.

But Chongqing’s growth model placed private companies at the margins. Mr Bo oversaw the detention of dozens of business owners as part of an “anti-mafia” campaign, while their assets were seized on the pretext of corruption — a popular move with ordinary Chongqing residents, but one which had a deleterious effect on investor sentiment. “Some people had violated the law, but others were just investors. When their rights and personal security were impacted, they left the city or stopped investing”, says Du Bin, a Chongqing real estate and hotel investor.

China’s Slowing Pains

After three decades of strong growth, the world’s second-largest economy has been slowing down. In this series the FT examines the implications for business and society.

Part one

The struggles of entrepreneurs

Part two

Data beyond the national GDP

Part three

Chinese dream readjusted for the middle class

Part four

FT reader responses

Explore more from the series here.

Private business now accounts for only 50 per cent of the city’s economic output, according to official estimates. Some doubt whether a new generation of entrepreneurs can emerge.

“In the last decade we have not seen large private enterprises making progress,” says Mr Du. “What we do see are government finance vehicles.”

The investment-led growth model has begun to run out of steam. With urbanisation now at 60 per cent, Chongqing is ahead of the national average, and infrastructure projects now generate lower returns. Chongqing’s growth rate fell sharply to 6 per cent last year, while state-owned carmaker Chang’an laid off hundreds of workers as sales fell 54 per cent.

The investment binge has left Chongqing with a huge debt burden, with state-owned companies’ liabilities equivalent to nearly 200 per cent of the city’s GDP, the OECD estimates.

The same combination of slowing growth and rising debt is seen nationwide. Chinese debt has risen to nearly 300 per cent of GDP in the last decade, with state-owned companies estimated to account for the bulk of the increase. Economists such as Mr Lardy argue that private companies tend to be more productive, which helps explain slower growth as more financial resources are channelled into the state sector.

“If President Xi continues to emphasise that the Chinese Communist party must control all aspects of China and pursue policies that favour state firms and hinder the more productive private sector, private investment will remain weak, leading one to expect a further deterioration in the pace of growth over the medium term,” says Mr Lardy.

While it has played a crucial part in China’s economic fortunes, there has been a darker side to the private sector’s rise. With a weak legal system in place, business owners gained protection through connections with local officials, who channelled resources to them, such as land, and overlooked taxes in return for bribes or stakes in their companies.

For many economists, the model established during China’s period of rapid export-led growth was often a form of crony capitalism. Business owners benefited from a “series of distortions”, argues Xu Bin of the China Europe International Business School, including a state-supported low exchange rate, weak environmental regulation and a lack of mandatory welfare provision for workers.

Some of the measures undertaken by the Xi government have been designed to end those distortions but the private sector has been disproportionately hit.

A fierce anti-corruption campaign launched by Mr Xi in 2013, which has seen the prosecution of tens of thousands of officials across China, has increased scrutiny of political-business ties.

Tighter control over officials allowed Mr Xi’s administration to press ahead with a nationwide crackdown on polluting industries, which saw thousands of companies shuttered, and a campaign to close excess production capacity in heavy industry.

The burden of both campaigns fell more heavily on private companies. Mr Xi has also centralised tax collection, reducing the ability of private companies to dodge VAT and social security contributions to workers.

The toughest blow, however, has been the choking off of funding. In 2016, following warnings that the country’s vast debt burden risked creating a financial crisis, Mr Xi’s administration took action. Officials targeted the shadow banking sector — less regulated forms of high-yield debt that had become crucial to private businesses as their share of bank loans decreased.

The sudden absence of funds led to a record number of debt defaults — until recently unheard of in China. Some 124 bond issues with principal worth Rmb121bn defaulted last year. Private companies accounted for 80 per cent of them. That dragged down growth, fuelling a primary Communist party fear — rising unemployment.

The series of defaults marked a turning point in official attitudes. As growth rates plunged last October, Mr Xi made vocal comments in support of private business. “Any words or acts to negate or weaken the private economy are wrong,” he wrote in a letter. He summoned several dozen private business heads for a meeting, telling them “all private companies and private entrepreneurs should feel totally reassured”.

The message spread beyond Beijing. This January, Chongqing Daily, the city’s government mouthpiece, published an admission that previous leaders had “crushed the rule of law and the private economy”, citing a government researcher as saying the city had missed a “golden period”.

Loncin’s Mr Tu accused a state-run company of owing him Rmb6bn in debt at the March meeting of the National People’s Congress, China’s rubber-stamp parliament.

“He wouldn’t dare to say that unless leaders supported him. It’s a sign that the new leadership is paying more attention to private companies,” says Chen Jianzhong, a former Loncin executive who is now a real estate consultant.

This year, the central government has pledged $298bn of business tax cuts and ordered banks to increase loans to small and microenterprises by 30 per cent.

But the move has coincided with continued calls for banks to reduce risky lending, blunting its impact. Mr Chen says the effort underlines how the country’s financial system continues to operate more on political than economic grounds.

“If politicians don’t come out to explicitly support a sector, people think that it might be cracked down on,” he says. “So banks won’t be willing to lend.”

The uncertainty is weighing on entrepreneurs such as property developer Alex Zhou, who has invested Rmb90m into transforming an abandoned state-owned factory complex in Chongqing into a trendy art district — precisely the kind of service business that officials say they want to encourage. He has yet to obtain a bank loan. And recently, local authorities backtracked on a Rmb10m innovation prize they had awarded him.

Weekly newsletter

Your crucial orientation to the billions being made and lost in the world of Asia Tech. A curated menu of exclusive news, crisp analysis, smart data and the latest tech buzz from the FT and Nikkei.

“We received a notice saying that we couldn’t take it because we are a private enterprise and, as this is national money, it should go to a state enterprise.”

Additional reporting by Wang Xueqiao

Photographs by Giulia Marchi

Do you do business in China? How have you experienced the impact of the slowdown? We’d like to hear your thoughts and personal stories in the comments below.

Comments