The confusing investment path to saving the planet

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When Cambridge university said this month that its £3.5bn endowment fund would finally pull out of fossil fuel investments, the fund’s chief investment officer Tilly Franklin said they were trying to “align our investment strategy with the science”.

Cambridge is hardly alone in this attempt. As companies, cities and even whole countries pledge to have net zero emissions before 2050 to help keep global warming from rising to dangerous levels, investors are increasingly asking whether their portfolios are climate-change friendly.

The Covid-19 pandemic this year appears to have only hastened that trend. Far from turning investors away from environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing, the crisis has heightened interest in sustainable portfolios in general. A survey this month by RBC Global Asset Management found that the pandemic had led more than a quarter of professional investors to place more importance on ESG considerations.

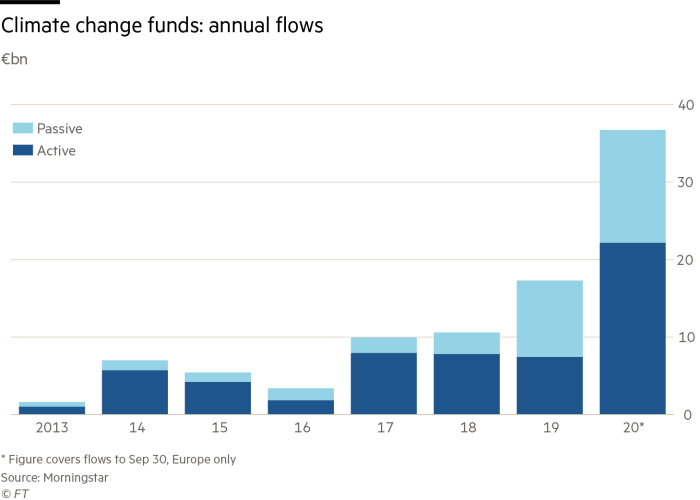

Climate-aware funds, a subset of the ESG funds that have been growing in popularity with investors, including retail savers, have attracted a larger proportion of the total flows into ESG funds this year than ever before. In the nine months to the end of September, new money going into climate-aware funds totalled nearly €37bn out of total sustainable fund inflows of €134bn — just over a quarter, data from Morningstar, the funds research company, show. The previous year, this proportion was just 15 per cent, with flows significantly lower too at €12bn.

“Climate change has never been so prominent in the minds of [investment] product manufacturers,” says Hortense Bioy, director of passive funds and sustainability research in Europe for Morningstar. “They’re responding to the ever-growing demand for products that help reduce climate risk in investment portfolios and/or promote the transition to a low-carbon economy.”

However, climate change funds can be confusing. There is not yet a standard classification: Morningstar has loosely identified six types, including low carbon, ex-fossil fuel and climate solutions, but it’s not always clear what sort of companies the funds hold.

Some funds simply invest in best-in-class companies: they might opt for the least polluting oil and gas company, or the traditional car manufacturer investing the most in electric vehicles. Or they might be investing in companies that have nothing to do with climate change as such but have set ambitious emissions targets: Retailer H&M and Microsoft, for example, are frequently held by so-called ex-fossil fuel funds. Or they might be investing in companies whose main business is cutting carbon emissions: an agritech company such as Trimble Navigation, for example, which produces software to make agriculture more efficient, or an alternative meat company such as Beyond Meat.

How green is your fund?

A big part of the confusion for investors trying to make their portfolios more climate-friendly is how their own approach may differ from that of the fund managers they use. Most climate-aware retail investors want to ditch oil and gas stocks from the portfolios as a first port of call. But this decision isn’t as simple as it might seem.

To start with, these companies have historically been good dividend payers so are a mainstay of many income funds. Ditching them, or the funds that hold them, could lead to a loss of income in the short term. That may not matter for many investors, who simply don’t want to hold such companies at all. But selling oil and gas shares may not damage the companies either. Bill Gates told this newspaper in 2019 that: “Divestment, to date, probably has reduced about zero tonnes of emissions.” Some fear that selling shares in fossil fuel companies may ease their conscience, but won’t effect change, as there are usually other less scrupulous investors willing to buy them.

But others argue that the real reason to divest is not because of your conscience, or to hurt the oil and gas companies: it is a rational investment decision. In a world where government regulation against heavy polluters is getting stricter and traditional oil and gas companies are seeing their business models under threat, it simply makes good financial sense not to invest in them, the argument goes. Many professional investors now believe that any investor who is not acting with climate change in mind could be exposing themselves to serious risk.

MSCI, the index provider, said this year that all investors — not just sustainable investors — should incorporate ESG principles in their investments to mitigate the risks of climate change. Its head of ESG, Remy Briand, predicts a “revolution” where within a few years it will become the norm for investors to hold ESG funds.

Yet, for now, it’s hard to calculate the risk of not having a climate-friendly investment portfolio. The UN’s Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) body has warned that financial markets haven’t worked out how to price so-called climate transition risk: the cost to companies adapting their business models to a low carbon environment and the government policies that will hasten that process along. It warns that not only will such policy change accelerate — with the bulk of it predicted to come in 2023-5 — it will be sudden and forceful as governments realise they should have acted sooner, causing a sharp shock for polluting companies.

Financial markets around the world have not priced in a forceful policy response to climate change in the near term. What if subsidies for oil and gas suddenly end, for example? Or cars with internal combustion engines are banned altogether? The PRI says that this forceful policy response is “a highly likely outcome, leaving portfolios exposed to significant risk”.

Shareholders flex their muscles

Divestment is not the only path that climate-friendly investors can take. Some are trying to engage more with companies they own to persuade them to do more to combat climate change.

Retail investors can take action, as well as institutions that are increasingly active. ShareAction, a UK-based shareholder group focusing on environmental, social and governance change at companies, offers training for individual members on how to ask constructive rather than aggressive questions at AGMs, for example.

It also pools its members to file calls for action at companies, with just 100 shareholders with £100 worth of shares each needed to file a resolution in the UK. In January, ShareAction filed the first ever climate-related shareholder resolution at a European bank, calling on UK-based Barclays to bring its lending in line with the UN Paris Agreement on climate change and publish plans to phase out funding to fossil fuel companies. While the resolution wasn’t passed by shareholders in May, ShareAction argued that the fact it got 24 per cent of the vote with a further 10 per cent abstaining was a “quite huge” level of dissent.

Twice weekly newsletter

Energy is the world’s indispensable business and Energy Source is its newsletter. Every Tuesday and Thursday, direct to your inbox, Energy Source brings you essential news, forward-thinking analysis and insider intelligence. Sign up here.

This choice between divestment and engagement helps to explain some of the confusion around climate change funds. A majority of so-called ex-fossil fuel funds, for example, do hold companies involved in oil and gas. This is often because fund managers are happy to back companies that are making more of an effort to transition to renewable energy, but still have legacy revenues. Iberdrola or Ene, for example, are often held in climate change funds though still derive significant revenue from emission-generating activities.

Other investors look beyond the debate between divestment and engagement and prefer to focus on positive solutions to climate change.

When Mr Gates criticised divestment as a climate change investment strategy, he was not advocating specifically for positive engagement; rather, he was encouraging investors to back solutions to climate change. His Breakthrough Energy Fund is backed by various billionaires, from Jack Ma, the Alibaba co-founder, to Richard Branson, the British serial entrepreneur, and it puts money into early stage, innovative companies focused on solutions to climate change. These include new technologies that can bring down the cost of solar and wind power even further; transmission technologies like high-voltage direct current (HVDC), which can transfer wind and solar power from where it’s created to where it’s needed; and smart, flexible power grid technology that can update old creaking systems and enable local producers of electricity to send it back to the grid.

Retail investors cannot access Mr Gates’s fund, which tends to back risky start-ups, but they can opt for clean tech or clean energy funds, which often invest in small companies with growth prospects, albeit with a higher risk profile than established groups.

Moral Money

For news and analysis about the fast-expanding world of socially responsible business, sustainable finance, impact investing, environmental, social and governance trends, visit FT.com/moral-money

With climate change investing in its infancy and interest so high, investment houses have been falling over themselves to launch products. That has led to fears of so-called greenwashing, where funds appear to be more climate-friendly than they really are. Regulators in the UK and Europe are on the watch for these cases. A new set of sustainable investing rules from the European Union that comes into effect next March is intended to clamp down on greenwashing and make ESG funds easier to compare by forcing asset managers to disclose more on their investments.

So investors who want to green their portfolios need to do their homework. But, at least in my personal experience of writing a book on the subject, researching climate change investment involves a lot of interesting questions. It forces you to consider your opinions, whether about divestment, the type of risk you want to be exposed to or the kinds of companies that excite you. Those who undertake a climate risk assessment of their portfolios stand a good chance of emerging not only as more disciplined investors but also, as I did, more hopeful about climate change, given the efforts being made around the world to solve it.

Alice Ross’s book, Investing to Save the Planet, will be published by Penguin on November 19.

Comments