Shepherd’s Bush in London: gentrification at last?

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

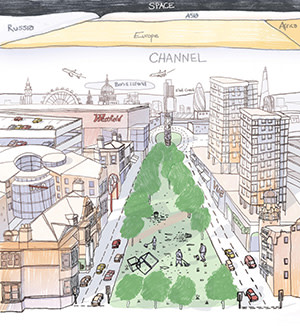

Shepherd’s Bush is not one of London’s lovelier districts. Sandwiched between the elegant suburbs of Holland Park and Chiswick, it is for the most part a tangle of unprepossessing Victorian streets clustered around a dystopian vision of the traditional village green – a windswept traffic island ringed by kebab joints and mobile phone shops.

There are pockets of prosperity – thanks largely to the army of BBC workers busily informing, educating and entertaining in nearby White City. In spite of last year’s closure of Television Centre, the broadcaster remains a big employer. But this is a corner of the capital that has remained until recently stubbornly, even gloriously, un-gentrified.

Take a stroll up the Uxbridge Road or into Shepherd’s Bush Market and you leave the manicured boulevards of Notting Hill behind. Parts could stand in for one of Cairo’s finer shopping streets. The Uxbridge Road throngs with Levantine restaurants, cafés and supermarkets. Just up from the Green stands “I Love Hijab”, a shop that sells imam-friendly jilbabs.

According to the poet and publisher Charles Boyle, who has lived in Shepherd’s Bush for the past 25 years, an impecunious magazine once photographed the writer Lawrence Durrell standing on a chair in the market to illustrate a piece about India.

“It stood in for the subcontinent rather well,” he thinks.

Until the 19th century, Shepherd’s Bush was open pasture, a place where drovers grazed their flocks for the last time on the way to Smithfield market. It emerged speedily between 1870 and 1900 as a piece in the jigsaw of late-Victorian metroland – one of the final suburban stops along the new Metropolitan Railway.

But even as the new City clerks moved in, the Bush remained on the fringe of social respectability. There was the lingering association with Urania Cottage, a pet project of Charles Dickens, founded by Angela Burdett-Coutts for destitute prostitutes, that was sited just west of the Green. The area never developed a settled character. This was always a transient place, a jumping-off point for new arrivals and those seeking to make their way in the capital.

Film-makers, writers and artists were among the first. The Gaumont film company opened Britain’s first purpose-built studios in Lime Grove in 1915. The BBC later took these over, expanding further with the completion of Television Centre in 1960.

Low rents and a profusion of venues, such as the Shepherd’s Bush Empire, made W12 a magnet for musicians. Both The Who and the Sex Pistols have their origins in Bush bedsits, and the mod band played many of their early gigs in the area. A survey by the website Guitarrockstar.co.uk in 2008 even dubbed W12 the top rock n’roll area in the UK, with one “star” for every 1,222 inhabitants.

And along with these itinerants came the immigrants. Somalis, Arabs, Poles, and Australians all descended on the Bush in a patchwork of communities. According to the 2011 census, nearly half the population is foreign-born and almost a fifth of households contain no one speaking English as a first language. Together, these ingredients give W12 its idiosyncratic flavour: halfway to Holland Park, halfway abroad; part cool cosmopolis and part predictable suburb.

Boyle has appointed himself the unofficial laureate of W12, collecting stories – true, truish and beyond true – about the area. A one-man crucible of urban myths, talking to him about Shepherd’s Bush is an endlessly amusing narrative.

One of his many flights of fancy is that the Bush has always been an unlucky place, and that this explains its air of relative deprivation. In the pre-railway age, he says, shepherds who grazed sheep there overnight often found one or two missing in the morning, and sometimes lambs were born with malformations.

Others have more prosaic explanations. Chris Hamnett, a professor of geography at Kings College London believes that 20th-century urban planners may be to blame.

“The real puzzle with Shepherd’s Bush is why it has been so slow to gentrify,” Hamnett says. Having studied the process by which successive London boroughs have attained middle-class respectability, starting with Pimlico in the 1960s and rippling outwards to more peripheral districts such as Peckham and Dalston, he believes that the Bush should have gone upmarket years ago. “It’s closer to the centre than places like Hackney, has excellent transport links and the right sort of Victorian and Edwardian housing stock that can be reconverted for single occupation.”

The answer, he thinks, may lie in the construction of West Cross dual carriageway built in the late 1960s, part of a subsequently abandoned scheme to construct an orbital motorway around central London. This horror – stretching to six lanes in some parts – cut the Bush off from Holland Park, demolished streets of Victorian housing and inflicted some of the worst urban blight in the capital. “It was a bit like throwing a Berlin Wall across west London,” he says.

Yet just as one might have encountered the occasional “von” in East Berlin, W12 has never been wholly free of well-heeled Sloanes. For all its lack of glamour, the Bush has long had a particular social cachet born of its proximity to prosperity.

The phrase “beating about the Bush” can in posh west London circles refer to the number of hardier upper-class types that trooped in over the past two decades, consoled by the presence of the Old Etonian clothing tycoon, Johnnie Boden (who is said to have brought his gamekeeper up from the West country to eliminate the urban foxes round his Shepherd’s Bush digs).

In recent years, however, the toff count has been climbing. Well-off hipsters and posh “Trustafarians” (apparently including Prince Harry’s on-off girlfriend, Cressida Bonas) are snapping up properties, drawn to the area’s theatres, decent ethnic eateries, numerous cheap fabric shops and, of course, the giant retail Death Star that is the Westfield Centre.

Opened in 2008, this £1.7bn steel-and-glass ziggurat is now Britain’s second largest mall by revenue. Built on industrial land to the west of the dual carriageway that had not been developed since the war, its 300-plus shops – as well as its cinema, bars and restaurants – have made it a destination for shoppers from across London.

“Westfield put Shepherd’s Bush properly on the map,” says Nick Alderman, residential development partner at the estate agents Knight Frank. “Before then it was still regarded as sort of Aussie territory.”

Hamnett agrees: “I think what we may have witnessed is the Shepherd’s Bush equivalent of the fall of the Berlin Wall.”

There has certainly been a “catch-up” in house prices. According to Savills, they rose 93 per cent over the past decade and 32 per cent since the 2007 peak – among the capital’s sharpest increases. A decade ago, properties in the Bush fetched 40 per cent less than they did in the leafier areas of Hammersmith to the south. Now that discount has narrowed to about 20 per cent.

It isn’t just estate agents that have been making hay. Developers have descended on the Bush. In addition to a £1bn expansion of Westfield, Stanhope is investing £500m in redeveloping Television Centre, a scheme that will include a branch of the hip media club, Soho House.

More controversially, there are plans to redevelop the market – the Bush’s grungy holy of holies. This £150m scheme involves the compulsory purchase of most of the existing pitches and some neighbouring retailers, including A Cooke’s pie shop, a piece of Goldhawk Road history dating from the 1890s, and Classic Textiles, which provided the fabric for cloaks in the first Harry Potter movie.

Although the developers promise to retain the market’s character, it’s hard to see how this can be done while constructing 200 new high-end flats on what is a cramped site. Many traders have protested and the local Labour MP, Andy Slaughter, has denounced the scheme as a “land grab by a get-rich-quick developer which is destroying independent small businesses and affordable homes”. The Labour party’s victory over the development friendly Conservatives may yet cast fresh obstacles in the path of the bulldozers.

Not everyone regrets these changes. According to Toby Young, a journalist who lived in the Bush from 1991 until 2008: “Anyone who complains about the area being taken over by yuppies should be stuck in a time machine and teleported into the middle of one of the gunfights that regularly used to break out on the Uxbridge Road on Saturday nights.”

Boyle prefers to focus on the subtler changes that gentrification has brought. He’s noticed that the tramp on his street is now a Frenchman with a cultivated palate: “I offered him a bag of cakes and croissants once and he would only take the pains au chocolats.”

Jonathan Ford is chief leader writer and a resident of nearby Brook Green

——————————————-

Buying Guide

● Shepherd’s Bush is close to three Tube lines, as well as the Overground railway

● It takes about 35 minutes to travel from Shepherd’s Bush to Heathrow airport via the M4

● The Metropolitan Police has recorded a fall in crime in the area, from 413 incidents in April 2013 to 323 in April of this year

● From April 2014, bills in the Hammersmith & Fulham area will be 3 per cent lower, and 20 per cent lower than eight years ago.

● Stanhope plc, the new owners of the BBC Television Centre, will spend £10m on developing growth in the area, from jobs to healthcare and transport.

What you can get for . . .

£500,000 A two-bedroom garden flat in a quiet residential street, close to main transport links.

£1m A four-bedroom townhouse with a garden, garage and off-street parking.

£2m A five-bedroom, three-bathroom terraced house with resident parking and a 60ft garden

——————————————-

Grotty, gritty – gentrified

Some years ago I irritated my brother-in-law by telling him that Williamsburg, the New York district in which he had just renovated a loft apartment, was “grotty”. He felt the word “gritty” better summarised the area’s edgy appeal.

Fifteen years on, of course, the whole place looks like Notting Hill. Its workshops and warehouses have been spruced up and the general nutcases who provided its air of crazed excitement have departed. Long gone too are my brother-in-law’s first tenants; a pair of artisanal glass blowers with a challenging business model.

The process by which districts gentrify is incremental. Before the well-heeled bourgeois descend en masse, it is necessary first for the young and trendy to identify an area that is merely grotty and by their presence add an acceptable dash of fashionable grit.

Identifying these up-and-coming districts in London has become something of a sport. A decade ago, it was somewhere like Camden. Now, as house prices have climbed, the sort of hipster artists and artisanal bakers who act as pilot-fish to the gentrification shark have been driven out of such berths and forced to swim further afield – to Tower Hamlets and Peckham.

Neal Hudson, an analyst at Savills, has produced some very rough data that allows you to see this process at work. He has used as a proxy for the trendy young the number of people working in media, culture and sport in each London borough between 2001 and 2011.

Engaged in cool – relatively poorly paid – professions, these are the sort of people who pioneer new districts before being effectively evicted by the financiers and seriously rich.

Hudson’s cool index seems to confirm popular perceptions. Camden, which was hip a decade ago, has landed on planet rich. East London boroughs such as Hackney, Tower Hamlets and Lewisham are where the cool are now heading.

As for the Bush, it’s a worrying picture for the impecunious hipster. Between 2001 and 2011, the number of media people in Hammersmith and Fulham declined by nearly 13 per cent. Of the 32 boroughs surveyed, only Kensington and Merton lost more. And that was before the closure of Television Centre. Looking for a place to blow some really cool glass? It may be time to head east.

Illustration by Luke Waller

Comments