Free trade is under fire but we must fight for its preservation

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

It has been a busy year for trade economists. The US and China have exchanged tariff increases, and the UK is deciding how to remodel its trading arrangements with the EU and the rest of the world after Brexit.

There is wider evidence of a backlash against free trade. Surveys show hardening public attitudes towards it in rich countries, particularly the US. While appreciating its benefits to consumers, Americans also increasingly blame free trade for reducing wages and destroying jobs. Fewer trade deals are being signed, ending an upwards trend that had lasted for decades during an unprecedented integration of the world economy.

Changes in trade policies, and the public attitudes that help drive them, do matter. It was long thought that more trade was inevitable, as transportation costs fell and technological improvements smoothed the way. But research has shown that policy changes and international co-operation played a crucial role. Globalisation was a choice, hence it could be reversed — at least partially — if rich countries decided to.

There is plenty of evidence on free trade’s beneficial effects. It has brought benefits to consumers through lower prices and greater product variety, while increasing aggregate gross domestic product. In lower-income countries it has also helped to lift hundreds of millions out of poverty. However, research has also provided support for public uneasiness about other effects of free trade: the gains are not evenly felt, and there have been losers.

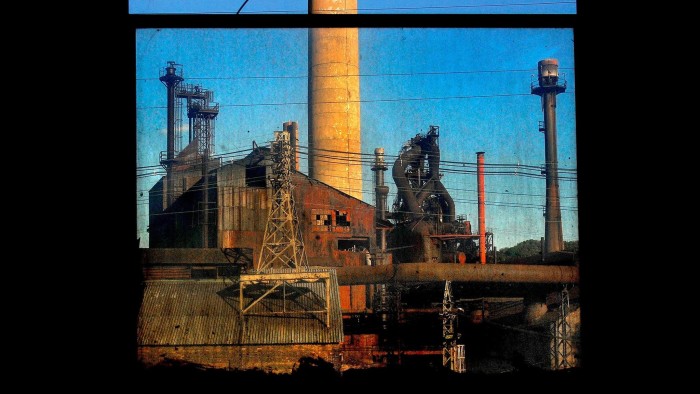

The impact of trade on regional inequalities within richer countries has emerged as a central issue. Perhaps the most famous example is the effect on the US labour market of China’s entry into the world trading system in the early 2000s.

Employment in the manufacturing industries that had to compete with a surge in Chinese imports was small overall, but highly concentrated in certain areas. When these industries shrank, the effects on local workers’ earnings and employment were not only large but also persistent. In the long run, we might hope that the displaced workers from those industries would soon shift into the growing new ones. In practice, this move appears to take at least a decade.

A similar cautionary tale has been told by research into free trade’s effects in a number of other countries. The regional aspect seems to be key. Alternative employment for affected workers is hard to come by because much of the local economy is affected; and people rarely respond by moving to more thriving areas instead.

This raises an important challenge. How best to reap the benefits of globalisation on the one hand, while protecting those who might be left behind on the other? In fact, these may ultimately be two sides of the same coin. If we do not work out how to mitigate the inequalities and disruptions that free trade can bring, it may be harder to sustain popular support for it.

All this means that trade policy should really go hand in hand with domestic policy. There are still big unanswered questions about how this should happen. The traditional welfare state often focuses on helping people through income top-ups. We need to know more about how to combine these benefits in an effective way with other kinds of interventions, such as retraining workers, assisting them in moving regions, or implementing “place-based” policies that explicitly recognise the geographic concentration of trade’s impacts by helping local economies.

I, and other participants in the Institute for Fiscal Studies’ Deaton Review of Inequalities, will be seeking solutions to these complex policy questions over the next four years.

The potential prize is to even out the effects of globalisation and, in the process, to maintain support for policies that can — if managed well — bring large and widespread benefits.

The writer is chief economist of the World Bank Group, on public service leave from Yale University

Comments