Why are so many Americans crowdfunding their healthcare?

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Isabella Masucci strode into hospital after a sleepless night. She carried a paper bag of prized possessions and bore two meandering scars on her hairless head. Instead of the princess dress she had wanted to wear, she was dressed in a T-shirt and pink leggings. They enabled easier access to the tube that hung down from a catheter under the skin of her chest, allowing doctors to load the toxic drug Dactinomycin into her heart. It was close to her 50th day of chemotherapy. Isabella is two years old.

Ten months earlier, after she began to experience balance problems and bouts of vomiting, a CT scan revealed she had brain cancer. Surgeons removed a tumour the size of a golf ball. Then came radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Now Isabella was back at a Florida hospital for more. She knew where to go, what to do, who she would see. “Dr Smith, Dr Smith,” she chirped as she walked towards the children’s cancer centre. Every so often she dropped her bag, scattering toys across the floor.

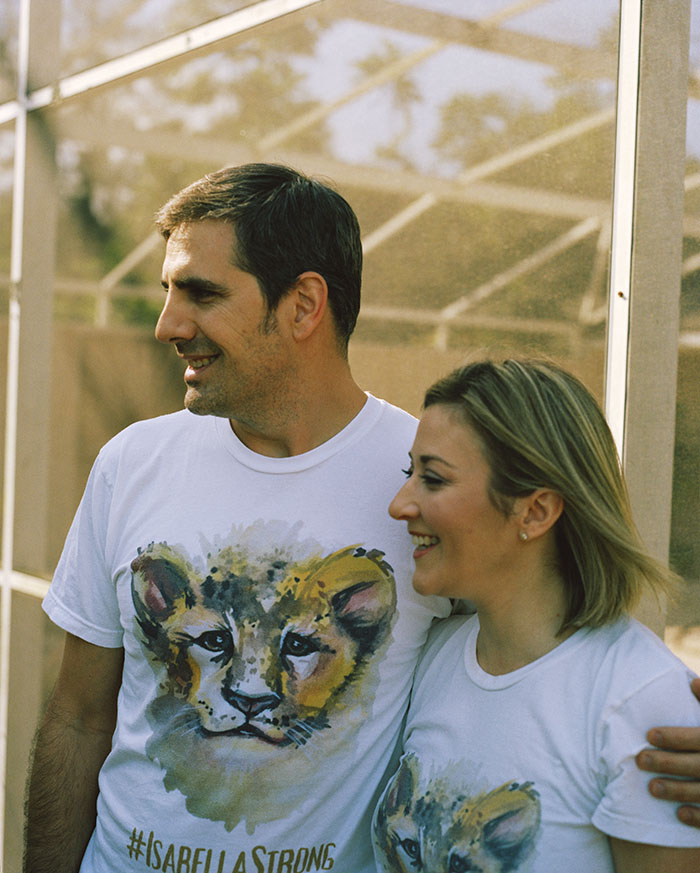

There to pick them up were her weary parents. For Claudia Koziner and Darren Masucci, the past year has been brutal. Each chemotherapy cycle begins with their daughter’s screams as a needle is jabbed into her chest. Once the treatment is over, she often succumbs to fevers and infections. They sleep for nights on end at the hospital.

Then there is the issue of money. In the US, where healthcare is not a human right, any serious illness comes with a financial shock. The average cost of hospital stays for cancer patients in 2015 was $31,390, according to government figures — about half that year’s median household income. The most common form of childhood cancer costs on average $292,000 to treat, says St Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee.

For the most fortunate Americans, these costs are covered by comprehensive insurance plans. For millions of others, they are a potentially crippling burden. After Isabella’s diagnosis, Koziner took unpaid leave to care for her daughter, reducing the family to a single income. She and Isabella were able to stay on the health plan provided by her employer, ensuring they did not join the 28 million Americans who lack any health insurance. Instead, they are part of a larger group that is underinsured. The family pay $15,000 each year as part of cost-sharing arrangements with the insurer, then have to cover everything it will not, ranging from protein shots to hearing tests to two-way ambulance trips that can cost up to $3,000.

Koziner’s retired parents offered to sell their house to raise funds, but the couple said no. Friends urged them to ask other people for help. “We were very sceptical,” says Koziner. “People are weird with money.” Eventually they relented — and joined the thousands of US families that have turned to online crowdfunding to help pay for medical costs. They had no idea what they would raise. “I was thinking 10 grand,” Masucci tells me. In fact, as Koziner says, “We made 20 grand in like a day or two.”

The total has now reached $109,245. Their page on YouCaring, a platform for fundraising for personal causes, has attracted 9,000 shares on social media and more than 1,000 donors. The money has come in tens, twenties, hundreds of dollars. Koziner has seen donations from alumni of her high school in Argentina. A woman from Dubai broke away from a trip to Disney World to deliver toys and essential oils to them in hospital. “A lot of the time we don’t know who these people are,” Koziner says.

They are not alone in relying on the kindness of strangers. YouCaring has helped its users raise more than $900m since 2011 and its momentum is building, with roughly $400m coming in over the past year. The company says close to half of its 350,000 active campaigns are related to healthcare and the fastest-growing category is fundraisers for cancer.

For Isabella and her parents, crowdfunding has alleviated financial pressure at an agonising time. “The fact that at least, at this point in time, we don’t have to stress about finances is huge,” says Koziner. “I don’t even know how we’d get by.” But its spread is also a symptom of a particularly American affliction: a flawed, costly healthcare system that offers some of the best care in the world to those who can afford it, while forcing millions of others to either plunge into debt or leave their illnesses untreated.

The rise of online fundraising for medical expenses brings its own troubling consequences, replicating some of the inequalities already dividing the country by forcing people to compete for funds.

“I remember the day we launched the YouCaring site. For me it was devastating,” Koziner says. “Because now the world knew that my daughter had cancer. You’re not just asking for money. You’re telling people what’s wrong.” Masucci says they had ended up stepping over boundaries they would have never imagined crossing. “So we’ve amassed a good amount of money through the YouCaring site and for that we’re grateful, but should it have to be that way?”

Online crowdfunding began in the late 1990s as a way for musicians and film-makers to raise money from fans. Within a decade it had begun to take hold for personal causes. The founders of GoFundMe, the sector leader, initially envisaged helping users pay for holidays and weddings. But by 2009 they began to notice people were using the site more to cope with crises, including medical emergencies. They embraced the trend. The company now calls itself “The World’s No.1 Site for Medical, Illness & Healing fundraising” and says it has raised $5bn for users globally since 2010.

It should be no surprise that healthcare proved fertile territory. Crowdfunding is also growing in the UK, Australia and Canada but is generally confined to treatments not covered by public healthcare systems. In the US it is often about paying for the basics. American medicine is big business and the US spends more on it than any other nation, yet it is the only developed country that lacks universal healthcare coverage. A fifth of US household spending went on healthcare in 2013, compared with just 4 per cent in the EU, according to Eurostat, a statistics agency.

Despite this, Americans are in worse health. Judged on measures including life expectancy and infant mortality, the US ranked last for healthcare outcomes among 11 high-income countries in a study last year by the Commonwealth Fund, a New York-based research foundation.

The medical-industrial complex, shaped by decades of policy grounded in a belief that private is better than public, is as vast as it is incoherent. For many patients, it is synonymous with dysfunction and unmanageable expense. According to a Gallup poll last December, 72 per cent of Americans believe the US healthcare system “has major problems” or is “in a state of crisis”. The strains are all too apparent. From 2005 to 2013, medical bills were the single largest cause of consumer bankruptcy in the US, according to Daniel Austin, a Northeastern University law professor.

“Who among us hasn’t opened a medical bill or an explanation of benefits statement and stared in disbelief at terrifying numbers?” asks Elisabeth Rosenthal, a physician-turned-author, in her 2017 book, An American Sickness . “It is easy to feel helpless.” Sites like GoFundMe and YouCaring offer the chance to regain some control. Their pages reveal campaigns for people facing strokes, leukaemia, Lyme disease, kidney transplants and muscular dystrophy. There are limbs lost, bones shattered and organs ruptured in car crashes and mountain falls and shootings.

It is on YouCaring that I find Yesenia Rosa, 34, an Orlando school teacher. She arrives to meet me holding a folder bulging with papers. When she opens it, medical bills slide out across the table. The first is a $722 charge for the biopsy last March that confirmed she had stage 2 breast cancer. “I was devastated,” she tells me.

She stopped working to cope with her treatment, and her school’s IT officer set up a crowdfunding campaign for her. For a time, the law required her employer to keep paying for insurance that covered core medical costs, including $111,578 for a round of chemotherapy. When that phase ended, Rosa had to cover the $906 monthly premium herself, a sum roughly equal to her rent. “If I don’t keep paying, they’ll cancel me the next day,” she says.

Other invoices on the table — for anaesthesia and a plastic surgery consultation related to her mastectomy — were not covered by insurance. Rosa is resigned to being pursued for the money by debt collectors. But crowdfunding, which has yielded $2,787 towards her $5,000 goal, has at least enabled her to keep her insurance. “It’s one quick way that everyone can help instantly,” she says.

Rob Solomon, GoFundMe’s chief executive since 2015, says his company is using social media to break up the old fundraising monopoly of traditional charities. “This notion of democratising campaigning is when the light bulb went off in my mind,” he tells me. “I said, ‘Wait a minute. This is the disruption. This is the transformation.’”

It is tempting to see crowdfunding as a new brand of philanthropy, filling holes left by the shortcomings of profit-driven healthcare. But it is not that simple. Crowdfunding is not the antithesis of the market. It is competitive in its own right — a sympathy market where sickness is on sale.

Claudia Koziner becomes tearful when I ask about her candid posts on Isabella’s health and her own emotions. “I have historically always been a very private person and my family’s always been very private,” she says, her voice cracking. “I’ve never been one to share too much with strangers.” Privacy is one thing successful fundraisers have to sacrifice. YouCaring advises campaign managers to think about which parts of their stories will “generate empathy”; to offer specific details and personal reflections; to post high-resolution photographs; and to provide regular updates.

Koziner understands what works. She has broadcast Facebook Live videos from the hospital and ends her frequent posts with tweetable hashtags such as #isabellastrong. “I don’t put everything, honestly,” she tells me. “You have to balance a little bit of the fun, the happy, the silver lining, because if not it’s too depressing.”

Others are uneasy about the demand for self-marketing. “You have to kind of make the appeal that you are a worthy subject for donations. It’s the commercialisation, the commodification of your illness,” says Jeremy Snyder, an associate professor at the Faculty of Health Sciences at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia. The business of healthcare turned the sick into consumers. Now crowdfunding is turning patients into products.

Not every product finds a market. Academics at the University of Washington Bothell who studied 200 GoFundMe medical campaigns found that nine out of 10 did not meet their goals, which ranged from $310 to $100,000. They netted on average just over 40 per cent of what they were seeking. Seven raised nothing at all. Last November, Bernie Sanders, the former Democratic presidential candidate, highlighted the story of a diabetic, Shane Patrick Boyle, who died after his GoFundMe campaign to pay for insulin reportedly fell $50 short.

Bioethicists have long wrestled with how public healthcare resources should be allocated when there is not enough for everyone. There is a loose consensus on the need to consider the cost-effectiveness of treatment, the gravity of patient needs, and individual financial circumstances.

There is no argument for distributing funds according to who is most telegenic. But that is what crowdfunding sometimes does. Daryl Hatton, founder of several businesses in the sector including FundRazr, views this as unavoidable. “Life’s not fair,” he says. “People will have these challenges and conditions even when they’re not attractive, they’re not the most fundable. It’s a bit of a popularity contest and there’s not much you can do about that.”

While crowdfunding platforms allow anyone with an internet connection to tell their story, there is no guarantee their message will be heard — or that it will resonate with funders. “People come at this thinking that [a successful campaign] is just about telling a really sad story or having a really tragic event,” says Nora Kenworthy, one of the University of Washington academics. “But we found plenty of really sad stories that weren’t getting any funding or were getting very little.”

Campaigns tended to do well when patients had discrete medical problems with comprehensible cures. Less successful were calls for help with terminal illnesses or chronic conditions such as heart disease, which did not carry the promise of a happy ending.

Crowdfunding may also perpetuate existing inequalities. Well-off people can tap into networks of well-off friends who have money to donate in a crisis. Poorer people tend to have ties to poorer people with less to give. Kenworthy and co-researcher Lauren Berliner warn that results can also be distorted by prejudicial notions of “deservingness” based on race, class and immigration status. “Crowdfunding seems to be best for people who are of a dominant social group who have fallen on hard times,” Kenworthy says.

To understand how people in one of the richest countries in the world ended up competing for healthcare funding online, it is instructive to listen to a Ronald Reagan recording from the early 1960s. A Hollywood celebrity moving into politics at the time, he spoke as Democrats were pushing to create a government medical insurance plan for the elderly, dubbed Medicare. Reagan tore into the proposal as “socialised medicine”. If Americans did not persuade Congress to reject it, he said, “behind it will come other federal programmes that will invade every area of freedom as we have known it”.

Reagan was voicing fears that have restrained federal involvement in healthcare since the Depression era. Healthcare industry lobbyists have played a central role in fostering the belief that the government should be kept at bay. Reagan had in fact recorded the message for the American Medical Association, a lobby group for doctors, which sent copies to physicians’ wives as part of its campaign to drum up opposition to Medicare.

“Physicians were very concerned that any [government] financing arrangement would bring control over their fees,” says Paul Starr of Princeton University, a leading healthcare historian. The AMA lost the Medicare fight, but in the past century the industry has defeated a series of other proposals for universal national insurance plans.

That clout has endured. No business sector, not even Wall Street, has shelled out more on lobbying than pharmaceuticals and health products. From 1998 to 2017 it spent $3.7bn influencing policymakers, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. Physicians have also preserved their generous earnings. Jobs in medicine and dentistry accounted for nine of the 10 highest-paying roles in America in 2016, according to Forbes, with anaesthesiologists earning an average salary of $269,600, surgeons $252,910 and family doctors $200,810.

The success of lobbyists partly explains why American spending on healthcare was worth 17.2 per cent of gross domestic product in 2016, according to the OECD. The second-highest figure was Switzerland’s 12.4 per cent; Britain came in at 9.7 per cent. “We’re somewhere close to the limit of what society can comfortably spend,” says Zeke Emanuel, an influential oncologist, academic and an architect of the 2010 healthcare reforms brought in under Barack Obama.

By the time Obama became president, voter frustration with the system’s dysfunction was such that the industry decided it had to support his push for change in order to influence it. Obamacare’s signature achievement was to reduce the number of uninsured Americans — but in doing so it cemented the primacy of private insurers.

The reforms were also meant to contain costs but their achievements on that front have been modest. Hospitals still have free rein to set prices for everything from urine tests and MRI scans to hospital gowns, and the bills keep ratcheting up. Most medical teams continue to get paid more for doing more, so they are incentivised to order procedures that are duplicative, unnecessary or pure invention. In 2016, a Utah hospital charged a father $39.95 for letting him hold his newborn baby.

Inscrutable pricing means that huge medical bills land without warning in the letter boxes of people already under great stress. “It’s not as if the [hospital] finance department steps up and says ‘Here’s a list of everything it’s going to cost you,’” says Darren Masucci, Isabella’s father. It is easy to see why a crowdfunding platform like YouCaring — which encourages users to “Take back control” of medical emergencies — is booming.

The queue begins before 3am on a Baltimore street. Pushed in wheelchairs or pushing walking frames, wearing prayer caps and hoodies, a few hundred people with cavities, cataracts, high blood pressure and diabetes form a line outside a convention centre. They have come from nearby streets and shabby towns two hours’ drive away.

Before the rise of online crowdfunding, charitable institutions that provide free medical care were one of the best hopes of treatment for people with limited or no insurance. The group in action in Baltimore is Remote Area Medical, a non-profit that has been running mobile clinics since it was founded in 1985 by an Englishman called Stan Brock. Inside the hangar-sized convention centre, volunteer medics buzz around their clientele.

One patient, Roosevelt Boone, stops to talk as he emerges from a dental exam. A bigger worry than his teeth is his need for a kidney transplant. He is leading the search for an organ, shopping among the donor laws and specialist hospitals of different states, managing three piecemeal insurance plans, and receiving dialysis three times a week. He tells me he considered crowdfunding but rejected it.

“I didn’t really want to expose my life to the world, number one,” he says. “Then, number two, there may be egos involved, because I didn’t really want to come out like I was begging.”

Boone’s patchy insurance coverage reflects the broader picture across the US. Half of the population have private policies provided by employers, and 7 per cent have plans purchased individually, including on Obamacare marketplaces. Government programmes for the poor, elderly and veterans cover about 35 per cent of the population.

Nine per cent have no health insurance, because they can’t afford it or don’t see it as a priority. According to the Commonwealth Fund, three out of 10 working-age Americans were underinsured in 2016 (meaning they had high out-of-pocket healthcare costs relative to their incomes) — 41 million people.

In the queue outside, Jan Nixon, 57, sits in a wheelchair with a handbag on her lap. She has broken an ankle bone but does not have the $2,000 to cover the 20 per cent share of the surgery costs Medicare will not pay. Her objection to crowdfunding is the fees the companies charge. “You can get a free website. True? So why are you charging for your idea?” Nixon demands. “You’re going to incorporate on my need? You’re going to benefit from my need? You want to make some money because I’m poor?”

GoFundMe used to take 5 per cent of donations, but stopped doing so in November for personal campaigns in the US. It now mimics YouCaring, charging a processing fee of 2.9 per cent of the amount raised plus $0.30, while encouraging donors to leave a “tip”.

Nixon is one of about 39,000 people Remote Area Medical saw at 76 separate clinics in 2017. Occasionally, grateful patients offer its staff a crumpled dollar bill, Brock tells me, and “we absolutely refuse it”. The organisation is sustained by annual donations of about $3m, which come in small denominations from members of the public. The rise of crowdfunding, however, shows there are donors out there looking for something different.

Ana Vitoriano, a 40-year old Florida consultant, helps businesses navigate health insurance for employees, but she is also a serial donor to people with coverage problems. She and her husband give up to $5,000 a year to crowdfunding campaigns and she says they offer something she cannot get from donations to old-school charities — a personal connection to recipients. “We’re not wealthy but I think we fare much better than most, so it’s something we can do,” she says.

Last year, when Vitoriano’s annual breast cancer screening uncovered an abnormality, she turned to Instagram to find moral support from women who had been there. She came across an account called “baldballerina”, which led to a YouCaring page with the same name. It told the story of Maggie Kudirka, a dancer with the Joffrey concert group in New York, who was diagnosed with stage 4 breast cancer in 2014 at the age of 23. Vitoriano sent a donation of a few hundred dollars, Kudirka wrote back to thank her and they began exchanging messages.

Vitoriano’s own cancer scare proved to be a false alarm. But she decided she could do more to help Kudirka. Knowing many people had insurance that required them to fork out hefty sums on expenses before their coverage kicked in, she told the ballerina: “You know what, I don’t have a child and I will cover your deductible [or excess] from this point forward for as long as I can afford it.”

That meant another donation last year of about $1,500 to Kudirka, who continues to need expensive post-chemo drug infusions. When I meet the ballerina at a dance studio near Baltimore, her hair has grown back and I ask about the name. “Bald ballerina just seemed to fit,” she says. “It’s easy to remember. Everyone’s like, ‘How can I find you?’ And I’m just, ‘Google bald ballerina.’”

Vitoriano is not concerned by the fees on crowdfunding sites. What she dislikes is the idea of giving to charities that could channel donations towards rent, wages or administrative costs. On YouCaring, she says, “the money you give is going straight to the person who needs it”.

Donors, however, need to be vigilant. Fraud on crowdfunding sites has taken hold. GoFundMe and YouCaring say the number of faked illnesses is negligible, but Adrienne Gonzalez, who tracks scams on her website GoFraudMe, says they are understating the problem.

Last November, an Alabama woman named Jennifer Flynn Cataldo was found guilty of fraudulently soliciting more than $35,000 on GoFundMe by falsely claiming she had terminal cancer. She hoodwinked friends and family, even convincing her young son that his mother was dying. “She took heartless advantage of their love as well as the compassion of strangers,” the Department of Justice said. She was sentenced to 25 months in prison.

As medical crowdfunding proliferates, America is still trying to work out how to feel about it. Rob Solomon, GoFundMe’s chief executive, tells me: “The reality of social fundraising is there’s a need out there, markets are efficient, and the market is saying that this is one of the most effective ways to get [people] help when they need it.”

Crowdfunding requests sometimes arrive in the email inbox of Zeke Emanuel, the Obamacare architect. “They are heartbreaking and they are bothersome and they are the kind of thing a mature system should not have,” he says. “Crowdfunding at this level is not an adequate solution to a systemic institutional problem for 320 million Americans. It’s a Band-Aid — and a very weak, small and not impressive Band-Aid.”

Polling by the Pew Research Center shows a rising number of Americans — now 60 per cent — believe it is the federal government’s responsibility to make sure everyone has healthcare coverage. But Donald Trump is moving in the opposite direction. Last December he signed into law a tax bill that neuters an Obamacare requirement for everyone to have a health plan or pay a penalty, one of several moves he has taken that experts say are destabilising insurance markets. The result is likely to be more vulnerable Americans in need of help.

Back in Orlando, Isabella Masucci settled into an adult armchair. She clasped her iPad, watching child stars on YouTube while the fluids in her drip were replaced by chemotherapy drugs. “It’s a Molotov cocktail of poison,” her father says.

Crowdfunding takes its own toll on those it helps. It is a sad, painful, essential form of salvation. “I don’t want to suck off the teat of society,” says Masucci, but he adds that healthcare’s “greed machine” left his family with little choice. He does not expect the government to pay for medical care, but believes it could make crowdfunding unnecessary by reining in spiralling costs. “Then we’ll take care of what’s important. The future of our country,” he says, gesturing to Isabella.

Later that day she would return home. Her parents would pull on toxin-resistant gloves to change her nappy and she would don her princess dress. The bills would keep stacking up and the next morning she would be back for more.

Barney Jopson is the FT’s US policy correspondent

How do you feel about medical crowdfunding? Have you ever donated towards the medical needs of someone you know? Please let us know in the comments below

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments