Emerging economies face rising interest rates as capital flows ebb

Simply sign up to the Emerging markets myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The vast wave of monetary stimulus that has kept emerging economies afloat since the coronavirus pandemic hit earlier this year has begun to ebb, just as pressure mounts on these countries to finance their recovery and their huge build-up of debt.

The combination risks creating a damaging spiral of falling currencies and rising borrowing costs, triggering debt crises and defaults, economists have warned.

“External financial conditions have stopped loosening and maybe tightened over the past month,” said Adam Wolfe, emerging markets economist at Absolute Strategy Research.

Foreign investors have become net sellers of emerging market stocks and bonds in recent weeks, following a period of capital inflows after the panic selling that gripped markets in March. The reversal of capital flows will make domestic funding conditions tougher for many countries, Mr Wolfe said.

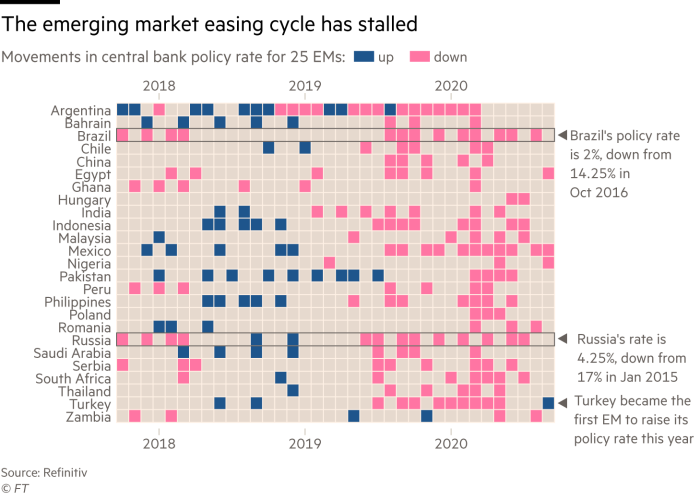

The changing conditions mean that central banks that loosened monetary policy as part of their initial response to the crisis will find it harder to do so again. The number of banks lowering rates shrank to a trickle in September, after a wave of loosening in the second quarter of the year, according to a Financial Times analysis of monetary policy in 25 developing countries.

Of the economies in the analysis, only Mexico, Egypt and Nigeria lowered their policy rates in September, the smallest number of rate cuts since April 2019 and down from a peak of 20 in March.

Central banks in Turkey and Hungary raised interest rates in late September, the only banks among the 25 to tighten policy this year and the first sign that the loosening cycle may be about to reverse. Hungary left its main policy rate unchanged but raised its influential one-week deposit rate for the second time after its currency depreciated steeply.

In normal times, central banks typically raise rates to ward off inflation, which can be stoked by a weakening currency. But the collapse in economic activity since the pandemic began means that subdued demand will probably keep pressure on prices to a minimum.

Today, central banks worry about exchange rates for other reasons. A devaluing currency means lenders will demand higher returns on government bonds, making borrowing more expensive at a time when many national budgets are under severe strain.

Along with the lira and forint, several other emerging market currencies have depreciated sharply during the crisis, including those of Brazil, South Africa and Russia.

“Falling currencies in emerging markets raise the fear of further devaluation and add risk premia to all kinds of credit spreads,” said Robin Brooks, chief economist at the Institute of International Finance. “They are a sign of tightening financial conditions and potential funding issues.”

Not all governments face such challenges. In China, Taiwan and Vietnam, for example, the virus has been brought under control and economic activity is close to or above pre-crisis levels, leaving governments less vulnerable to a tightening of global financial conditions.

“Asia is very different from the rest of [the emerging markets],” said Johanna Chua, head of Asia economics at Citi. “Many countries are self-financing so they don’t have the same constraints as other emerging markets.”

Other countries have so far kept going by taking on large amounts of new borrowing. Overall, emerging economies raised about $145bn on international bond markets between January and September, and an additional $630bn on domestic markets, according to the IIF. That is about $135bn more than the same period last year.

They have been able to borrow so freely thanks partly to the trillions of dollars of liquidity poured into global financial markets by the US Federal Reserve and other advanced economies’ central banks. Many have also benefited from emergency lending from the IMF and World Bank, while others have been able to draw on relatively deep domestic financial systems, where banks, pension funds and others can be relied on to buy government bonds.

But it is their historically low policy rates that have underpinned the borrowing spree.

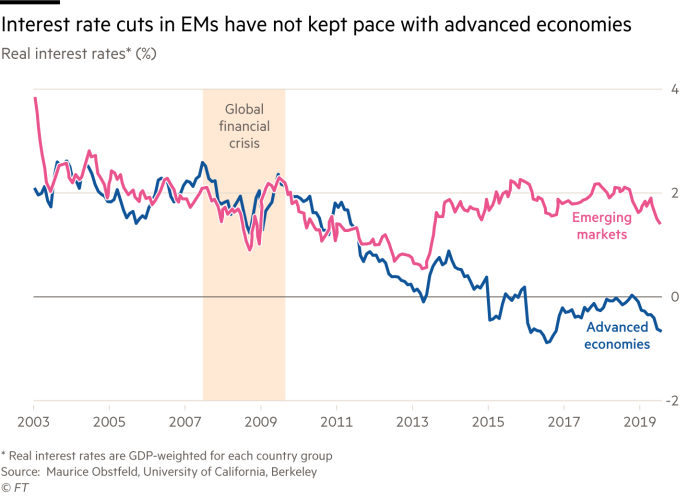

Policy rates are at or below 1 per cent in seven of the 25 countries surveyed — even though, adjusted for inflation, they have not fallen by as much as rates in advanced economies in the decade since the global financial crisis.

In places that have in the past been known for their relatively high rates, such as Brazil and Russia, rates are at all-time lows. Several governments that previously sold longer-dated bonds have borrowed much more cheaply during the pandemic by issuing short-term bonds, a risky strategy because they must be repaid quickly.

If interest rates remain low and economies bounce back quickly, the gamble will pay off, analysts said. But if interest rates rise and economies fail to regain economic ground, this could lead to serious trouble.

Jeromin Zettelmeyer, deputy director of the IMF strategy, policy and review department, recently warned that the number of countries at high risk of falling into financial crisis had risen during the pandemic from three to eight among advanced economies and from 15 to 35 among emerging markets.

He cited an alarming expansion in budget deficits and a recent rise in borrowing costs, to the extent that a handful of countries had already lost market access.

“The increase in the risk of debt crisis over the short and medium term is going to be very high,” he said at a forum hosted by the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “If you lose market access, you are in trouble.”

Also speaking at the forum, Maurice Obstfeld, professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley, said that recent falls in nominal rates should not disguise the relatively high real interest rates in emerging economies compared with advanced ones, and that low real rates and cheap government borrowing may not be sustained.

“Where [emerging market interest rates] are going to go in the next few years is unclear, but we should worry about this,” he said.

Comments