Space mining takes giant leap from sci-fi to reality

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

A remarkable law took effect in Luxembourg in August. It provides a legal framework for private companies to exploit resources in space — a sign of the Grand Duchy’s plan to become a global leader for extraterrestrial mining.

Reactions to Luxembourg’s space ambitions have moved from incredulity a couple of years ago to guarded admiration. Mainstream space circles see the idea of an extraction industry on asteroids and/or the moon as a serious long-term proposition rather than fantasy.

Resources will be used in space, starting with water which can be split by solar power into oxygen and hydrogen fuel for spaceships. Metals for space manufacturing such as iron, tungsten and titanium will follow. Bringing precious metals to Earth is a long term dream.

Luxembourg has a history of investing in industries on the eve of take off. It built its economy on a formidable steel industry during the industrial revolution. Later, it moved into financial services, broadcasting and satellite technology, founding SES, the world’s largest private satellite operator, in the 1980s.

“We are convinced that the exploration and use of space resources will be necessary, in a first step to facilitate further exploration of outer space [providing fuel and other materials for spacecraft] and at a later stage to meet some of the needs down on Earth,” says Etienne Schneider, Luxembourg’s deputy prime minister.

Chad Anderson, head of Space Angels, a US-based company investing in the sector, says the recent flow of private finance into space resources is part of a surge of support for a range of innovative activities sometimes referred to as NewSpace. Many NewSpace companies are setting up in Luxembourg to take advantage of legal and financial incentives offered by its government.

Total private investment in commercial space ventures rose from $534m in 2014 to $3.1bn last year, notes Mr Anderson. “The type of investor is changing too,” he says. “It used to be a bunch of space enthusiasts looking to make an impact on the field. Now we are seeing more mainstream and institutional investors.”

“In our lifetimes we will see commercial space, including resources, developing into a multi-trillion dollar industry,” says Chris Lewicki, chief executive of Planetary Resources, a US asteroid mining company.

The options for extraterrestrial mining, the moon and asteroids, contain valuable raw materials, ranging from ice to metals. The moon is much closer to Earth, in a nearly circular orbit 240,000 miles away. Radio communication is easy and the lunar surface has been mapped in detail. Asteroids, far further away, have more eccentric orbits and less well understood geology.

That said, the moon exerts significant gravitational pull, about one-sixth that on Earth. Smaller asteroids have very little gravity, which would make it easier to remove materials after mining.

The moon has such key materials as extractable ice near the poles. A longer term lunar prospect is helium-3, scarce on Earth and potential fuel for nuclear fusion reactors later this century.

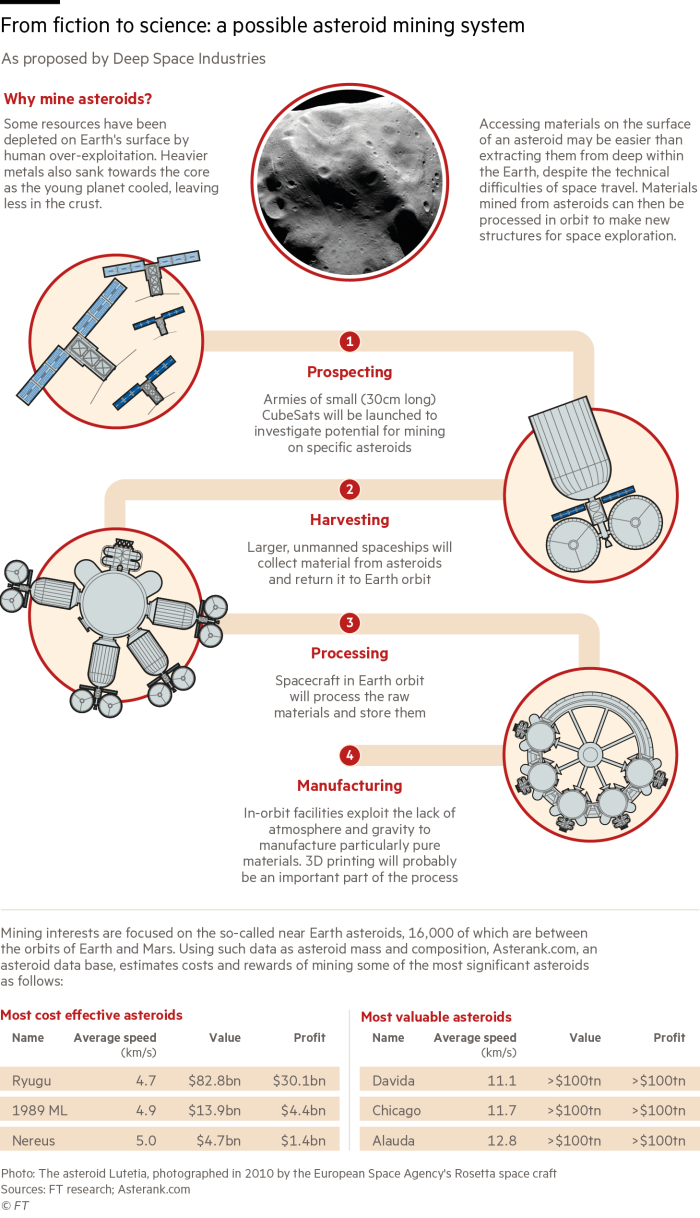

The 16,000 near-Earth asteroids are diverse in composition. Mining companies could select targets in which sought after materials are richly concentrated.

“The moon is so much more accessible than asteroids,” says Kyle Acierno, European managing director of ispace, a lunar resources company based in Japan. It aims to launch its first probe to the moon on an Indian rocket next March. “We are confident that mining on the moon will take place before mining asteroids,” Mr Acierno adds.

The two most prominent asteroid mining ventures are Planetary Resources and, also of the US, Deep Space Industries. Both have European operations in Luxembourg.

“To a certain extent asking ‘the moon or asteroids?’ is a false choice, like asking whether it is better to put a new museum in New York or Paris,” says Mr Lewicki. “People could do both.”

Space mining stories have featured the extraction of precious metals from asteroids but the first resource exploited will almost certainly be ice. This can be used to provide the water needed by various space activities. Water’s most valuable application will be for it to be split into oxygen and hydrogen to provide fuel for spacecraft.

The fruits of space mining will be used initially in orbit rather than brought to Earth. There is scope for converting metals into components for spacecraft using 3D printing and robotic techniques. Manufacturing in orbit from materials available in space promises to be more economical than making things on Earth and lifting them into orbit.

Exploiting precious metals such as platinum and gold — richly concentrated in some asteroids — probably lies several decades in the future.

Uncertainty over the legal basis of space mining — do private companies have the right to extract and make money out of celestial bodies that do not belong to them? — has receded in recent years. The United Nations Outer Space Treaty, now 50 years old, provides the basic framework on international space law. Its declarations include: “The exploration and use of outer space shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all countries and shall be the province of all mankind; outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by . . . any means.”

Legal scholars have been divided on whether this permits lunar or asteroid mining — an activity that really was sci-fi when the treaty was drawn up. In 2015, President Barack Obama signed the Space Resource Exploration and Utilisation Act, giving any US company or person property rights over natural resources from outer space.

Luxembourg went further this year with its law “ensuring that private operators can be confident about their rights on resources they extract in space”. The law provides that space resources can be owned by anyone, not just by Luxembourg citizens or companies.

Mr Lewicki thinks the time for prospecting and extraction could be little more than a decade away, comparable with the development of a large terrestrial mining project. More cautiously, Mr Schneider, for Luxembourg, believes two decades is a more likely estimate.

Comments