Airlines face long-haul to carbon-free flying

Simply sign up to the Airlines myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Carbon offsetting flights used to be the domain of the wealthy or eco-warriors looking to assuage their guilt. But now even low-cost airlines are taking action to cut their carbon footprint as the aviation industry comes under pressure to reduce emissions.

EasyJet last week became the first big carrier to start offsetting carbon emissions on flights across its whole European network, trumping recent announcements by British Airways and Air France to offset all domestic flight emissions from next year.

It comes as airlines have realised they need to respond to the growing “flight shame” movement.

Over the past two months both International Airlines Group, which owns BA and Aer Lingus, and the Australian carrier Qantas have pledged net-zero carbon flying by 2050.

Meanwhile, the German airline Lufthansa plans to introduce a business fare that will automatically offset emissions for corporate customers flying in Europe.

But despite carriers vying with each other to demonstrate plans to decarbonise, the industry has come under fire for simply “greenwashing” by purchasing offsets, rather than reducing their actual emissions.

EasyJet’s announcement immediately drew fire from environmental groups, with Greenpeace saying the move was a “jumbo-size greenwash”.

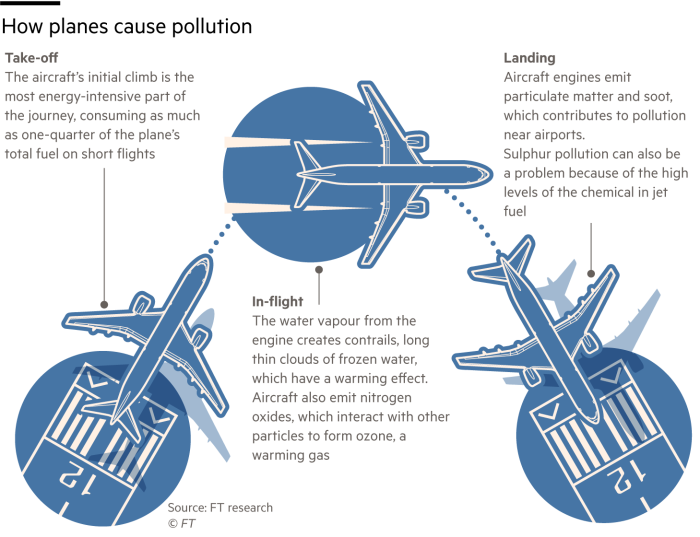

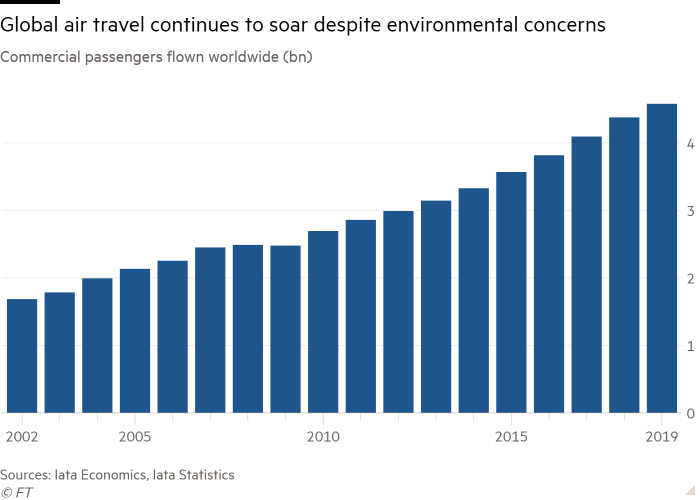

The criticism highlights the huge problem for an industry, which is one of the fastest-growing source of emissions in Europe but one where long-haul carbon-free flying is unlikely to become a viable technological reality over the next few decades, if ever.

“This is one of the most difficult industries to decarbonise,” said Rafael Schvartzman, regional vice-president for Europe at Iata, the international airline association.

The airline industry is expected to be the biggest source of demand for carbon offsets, due to an industry-wide agreement that pledges to offset the growth in international aviation after 2020.

That deal, called the UN Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation, or Corsia, will introduce voluntary carbon offset purchases in 2021, and these will become mandatory in 2027. It has set a general target of a 50 per cent cut in emissions from 2005 levels by 2050.

However, carbon offsets — which can be purchased by a polluting company or individual to compensate for their emissions — have been criticised because some projects fail to deliver the emissions reductions promised.

Moreover, there is usually a delay of several years, or even decades, between when the purchase is made and when the carbo -dioxide is sequestered.

In some cases, the offsets that are purchased are used for projects that would have taken place anyway — and thus should not be counted as providing “additional” emissions reductions.

“Airlines paying others so that they can go on polluting is not a solution,” said Andrew Murphy, aviation manager at Transport and Environment, a campaign group.

Johan Lundgren, easyJet’s chief executive, was upfront last week in his acknowledgment that carbon offsetting was only an “interim measure” in addressing environmental concerns. The budget carrier is working with aircraft manufacturers to develop electric and hybrid planes.

Airbus is at the forefront of developing hybrid electric aircraft, with its E-fan-x demonstrator due to fly in 2021, and a variety of all-electric urban taxi concepts.

“These are new aircraft and not available today. They will require work to bring that technology to commercial aviation,” said Glenn Llewellyn, vice-president of zero emissions technology at Airbus.

The aircraft manufacturer is targeting the mid-2030s for the first jet powered by a combination of generator and gas turbine. This is likely to be a more limited range aircraft than the current single aisles being used by low-cost operators such as easyJet.

In the short-term, the industry believes a combination of offsetting, improving flight paths, more efficient aircraft and sustainable fuels will help to reduce aviation emissions.

Many believe that one of the most promising areas is alternative low-carbon fuels, which could be used in existing aircraft, but with a lower carbon footprint. These include biofuels, which can be made from plants, waste or algae, and synthetic fuel, a substance resembling jet fuel that can be manufactured using renewable energy.

Iata has set a goal of 1bn passengers on flights powered by a mix of conventional and sustainable jet fuel by 2025. In 2017 there were 100,000 of these flights.

Airbus’s Mr Llewellyn said the company has certified all its existing aircraft, those in service as well as those on the production line, to use 50 per cent synthetic fuel, which would halve a jets emissions during flight.

Made through a process known as direct air carbon capture, “this is a technology we are very excited about”, he said.

“The process has been fully demonstrated. It creates a hydrocarbon which can be refined into aviation jet fuel. Because it is extracted out of the air, and you emit it again when you fly, the overall effect is a net zero CO2 emission flight.”

The challenge will be to create the right infrastructure and production capacity to make the industry viable. Currently, the costs of hydrogen are still too high, for example. The aviation industry has called for government support to help grow the sustainable fuel market.

In the meantime, it is clear that even for the next 20 to 30 years, carbon offsetting will have to play a huge role in the aviation industry to reduce emissions.

Willie Walsh, chief executive at IAG, the first airline group to pledge to be net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, noted at the group’s capital markets day this month that while sustainable biofuels will be “part of the solution in the longer term”, it will not be enough to offset the increase in CO2.

As part of its plan to get to net-zero by 2050, IAG said 18 per cent will come from sustainable biofuels and 39 per cent through new aircraft and more efficient operations, but as much as 43 per cent will still come from offsetting and emissions trading schemes.

Comments