Women going freelance face bigger gender pay gap

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Women have increasingly turned to self-employment to escape some of the rigidities of corporate life, only to encounter setbacks of another kind. For freelancers, the gender pay gap is wider and may prove harder to close than if they were employed. Moreover, the control over their lives, for which they may have sacrificed pay, is under pressure if they need to chase work.

In the past decade, more women have joined the self-employed workforce in search of better pay, improved working conditions and flexible hours. A study this year by IPSE, a UK association of independent professional and self-employed people, found a 63 per cent increase since 2008 in skilled women choosing to freelance.

The 21st-century workplace and the rise of the gig economy, it turns out, bring their own challenges on remuneration, with a gender pay gap that is wider than the average found in employed occupations (see chart).

According to the OECD, a club of mostly rich nations, the US and Poland have the biggest pay gap among the self-employed, both at 56 per cent.

Even Belgium, the country that has been the most successful in the developed world at tackling pay inequality between men and women, has found the self-employed gender gap stubbornly high.

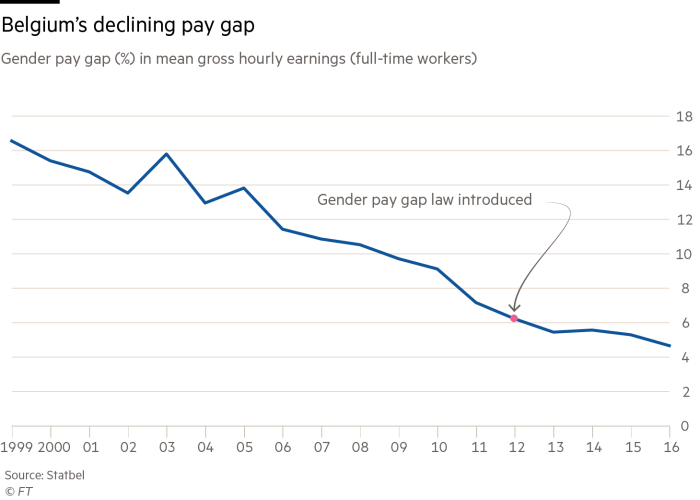

In Belgium, men on average earn 4.6 per cent more than women in full-time occupations, according to government agency StatBel. This is one of the smallest gaps in the world and is down from 15.4 per cent in 2000, and 7.1 per cent just before a law was passed to mandate pay gap reporting by companies. By comparison, the median gap in the UK stands at 16.4 per cent (see chart).

In 2012, the Belgian pay equality law made it mandatory for all enterprises with at least 50 employees to report on their gender pay gap every two years. A similar law was enacted more recently in the UK but it applies only to public bodies and organisations with at least 250 employees.

The Belgian companies must publish details of how they intend to narrow the gap, and female employees can ask for a mediator to investigate claims of wage discrimination.

When it comes to Belgium’s self-employed, however, the gender pay gap is 30 per cent, according to data from 2016, a figure that has been virtually static since 2010.

Katia Segers, a member of the Flemish parliament and the Belgian senate, says: “In today’s modern economy, what you see is more young people starting out as independent or freelance workers developing “slash careers” [simultaneous jobs].

“Then, of course, the gap is huge because they don’t belong to a company [that] would be forced to publish their wage figures.”

When it comes to entrepreneurship, according to the OECD, women setting up a business attract less funding than men, and suffer from the general lack of support for founders.

“Female entrepreneurs often have lower levels of capital and are more reliant on owner equity and insider financing than men, and women typically face greater challenges in accessing loans and debt financing,” said the OECD in a 2017 report, adding that much of this was driven by gender discrimination.

As a result, female freelancers end up in a “glass cage”, as a 2016 study in the New England Journal of Entrepreneurship put it.

“Regardless of the parity in education, work experience, number of hours worked or occupation, women earn less than men in self-employment,” the study found, adding that women’s ability to narrow the gap is limited.

The gig economy has exacerbated the situation. Sarah Kaplan, director of the Institute for Gender and the Economy at Rotman School of Management, Toronto, says: “Because these jobs lack many legal, social and financial protections, they are not benefiting women”.

For those women looking for greater control over the quantity and timing of working hours, she warns: “[Such] jobs often lack real flexibility. [People] are penalised if they don’t make themselves available for extended periods of time or decline certain jobs.”

Research on gig work sourced via online platforms suggests that the gender wage gap can vary between 7 per cent and as much as 37 per cent, depending on the sector.

“Where there are no group-level protections, it is hard to [be] sure that people are not discriminating in what they pay people of different genders,” says Prof Kaplan. One policy solution would be to make public the average fees for services via the government or industry associations, she suggests: “People would know if they are charging an adequate amount or being paid an adequate amount” — although she acknowledges this is “uncharted territory.”

Caitlin Pearce, head of the Freelancers Union in New York, echoes the point: “Creating channels for pay transparency is essential for independent contractors who establish their own rates and must constantly negotiate contracts with clients.”

She points to the emergence of online rates databases and informal rate guidelines compiled by workers’ alliances: “Facilitating these conversations with peers can be tricky but it is necessary to understanding industry standards and how and when you can raise your rates.”

Letter in response to this article:

Freelancing is a huge win for many women / From Dena McCallum, Founding Partner, Eden McCallum, London WC2, UK

Comments